Note: This post is the first in a two-part series. Read the first post, exploring collaborative strategies for creating change here.

Scholarly communication doesn’t work well enough for enough stakeholders. But why is that, exactly? What are the root causes? How do these point to solutions?

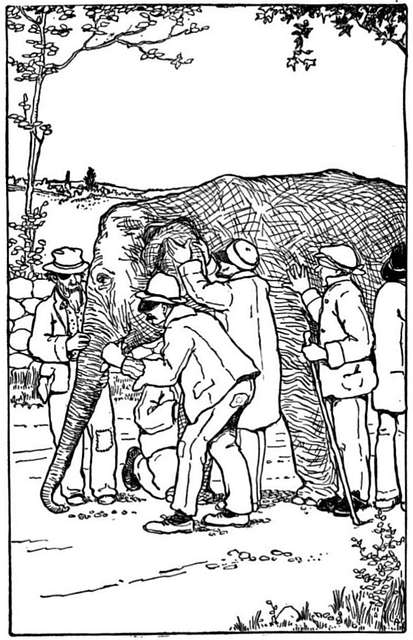

There is a parable common in the business world about a group of people who’ve never seen an elephant and must identify the animal by touch alone — one feels the leg and thinks it’s a tree trunk, another finds the tail and identifies it as a rope, someone else touches the tusk and describes it as a spear.

Like the story of the elephant in the dark, those of us working scholarly communications often point to different issues depending on our role within the industry and what parts of the system we happen to touch. For some the issue is speed, for others cost, accuracy, transparency, reproducibility, completeness, integrity.

All those problems are real. But if we turn on the lights and examine the complete picture, the underlying issue is clearly system-wide, and firmly anchored in the linked problems of process and incentivization. What’s undercutting scholarship isn’t simply a tree, or a rope, or a spear; it’s an elephant.

A system of interconnected challenges

The problems with research communication can feel like a never-ending litany. But they can generally be traced back to the twin obstacles: a research reward system that doesn’t align with scientific goals, and a journal publishing industry seemingly content with slow, inequitable norms of the previous century that has commercialized every aspect of the process in ways that limit innovation. The impact of those two issues shows itself in myriad and sometimes surprising ways.

Journal publishing is very costly. Subscription costs continued to rise and even now, in the era of open access, article processing charges (APCs) can cost authors as much as $14,000 for a single article. And that’s without taking into account the costs in researcher time and effort associated with publication. “Shopping” research articles from journal to journal can take months and forces researchers to spend hours completing similar submission forms and making cosmetic changes. An estimated $230 million USD were lost in 2021 alone due to reformatting articles for resubmission at different publications. As much as $2.5 billion USD could be lost between 2022 and 2030 solely due to reformatting articles after a first editorial desk rejection. As those of us who have worked in publishing know, reformatting is only one of the many print-based inefficiencies remaining long into this digital age.

Journal article requirements still restrict the length, formats, data, and even bibliographies as if print were still the primary vehicle for research communication. Even the HTML view of an article doesn’t offer much more interactivity or depth than a PDF. If the underlying data are shared, they are frequently in supplemental files that are not indexed or machine-readable. This information will effectively disappear in the AI era. That in turn limits the ability to replicate and build on that work.

That is only exacerbated by the artificial divide between conducting research and sharing it. Historically, print-based publishing meant that such a gap was unavoidable: print publications could not contain datasets and other supporting materials so the work was reduced to a description of the science. None of this is necessary in the digital era, yet these gaps remain.

Researchers are pushed to publish in high impact journals at the expense of risk-taking, jeopardizing innovation. In addition to incentivizing behaviors that may not produce the best science, the current publishing process is very slow. The number of experiments done for a single article has increased and the time from submission to publication has not been reduced significantly in the digital era as expected.

Meanwhile, journal-facilitated peer review remains the standard vetting process for many research leaders, even though it is a relatively recent practice that has never been a particularly effective filter. There is evidence of bias and it delays publication of the work for months or even years.

Creating meaningful system-wide change

For the past quarter century stakeholders including publishers, funders, institutions, and researchers, have attempted to tackle this web of interdependent challenges individually and in isolation, each coming at our particular version of the problem from our own limited perspective. That hasn’t worked and little has changed.

Funder policies designed to advance openness often lack any practical means of monitoring or enforcement, rendering them ineffective. “Born” Open Access journals launched with a focus on the problem of public access and unfortunately replicated everything else about existing journals. This has contributed to the delay in solutions for the other problems in publishing such as print-based workflows and systems, high costs, slow processes, and closed peer reviews, while the invention of the APC inadvertently opened the door for large scale commercialization, exorbitant prices, and hybrid journals.

Preprint servers have normalized early sharing of manuscripts prior to peer review. But the preprint format is perceived as inferior, even to journal articles, available only as a flat PDF, without shared data and other outputs. While addressing, in part, the issue of speed, they have reduced reproducibility. Preprints have succeeded in offering an alternative to sharing work only through journal articles, and journals have ceded this early publication space to preprints, offering an opportunity to build a new ecosystem based on early sharing.

Public trust in science increases when underlying data are shared. But many datasets are made available in formats and file types that are not reusable, failures of metadata limit discoverability, and a lack of information on the methods and code makes the data less useful. Instead of valuable high quality data lakes capable of spruing new discoveries, we are ending up with individual, isolated, and hard-to-maintain data graveyards.

We can imagine a new paradigm emerging from the increased emphasis on preprints and policies requiring data sharing. Early writeups that include links to all relevant outputs (like datasets) hosted in their appropriate repositories with persistent identifiers would go a long way towards improving speed, reproducibility, integrity, and broader impact. Preprints with data and other outputs is an achievable goal in our current state.

But real, big-picture, elephant-scale progress is going to take intentional cooperative action. At Stratos, we specialize in building connections across institutions, funders, publishers, and other stakeholders with shared goals and a willingness to reimagine and rebuild the systems of conducting, communicating, and celebrating research in ways that reflect the real needs and values of research. Stratos is working with the National Academies, influential funders, and innovative builders and researchers to build this new paradigm. Join us.